Yahara's Legacies

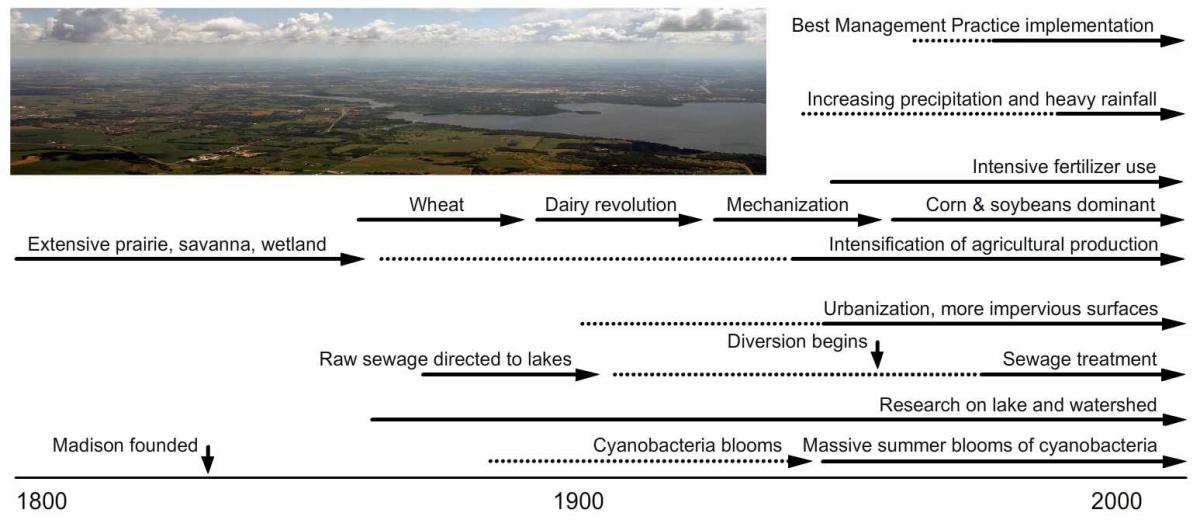

Changes in culture, values, technology, and public policy, as well as pivotal events, have influenced the Yahara Watershed. Looking ahead to Yahara's future requires understanding the legacies of its past.

Notable legacies include those of Yahara's early inhabitants and settlers, its sewage history, agriculture, and urban growth, which are highlighted in the timeline below.

Early Inhabitants

The Yahara Watershed's first human inhabitants likely arrived on the heels of the receding glaciers around 12,000 years ago. They found the region's soil rich, and its lakes and wetlands abundant with fish and other resources, which persuaded these nomadic hunter-gatherers to settle here.

Archaeological evidence, such as effigy mounds, and Native American oral traditions indicate this region was the spiritual center of these early cultures. The land ultimately became home to the Ho-Chunk tribe, who referred to it as Dejope, or the Four Lakes region.

The Ho-Chunk managed and used Yahara's land through prairie burning, hunting, fishing, and agriculture, practices which left a mark on the region's landscape and ecosystems, although to a lesser extent than those of the coming Euro-American settlers.

When the influx of Euro-American settlers began with the arrival of fur traders in the 17th century, trade, disease, and conflict dramatically altered Ho-Chunk society. Eventually, they were forcefully removed from the region.

The Sodbusters

The permanent settlement of Euro-American settlers in the 1820s led to significant changes in the Yahara Watershed. By 1880, settlers had converted about 75% of the native prairie and oak savanna landscape to cropland and pasture (today's percentage is lower, since urban land has replaced some former cropland). This conversion from erosion-resistant prairie sod to tilled, bare ground led to substantial erosion.

Farmers cultivated primarily wheat, because it was relatively easy and cheap to produce. Grist mills produced flour for mostly local markets, until the railroads enabled exportation in the 1850s.

By the 1870s, wheat disease, market pressure, and soil nutrient depletion (caused by the continuous wheat coverage) had driven Yahara farmers to diversify their crops. Following groundbreaking research at the University of Wisconsin, dairy emerged as a way to replenish depleted soil nutrients, via the use of manure as fertilizer, and to provide farmers with more reliable income.

Still today, dairy operations dominate Yahara's agricultural landscape.

Madison’s Battle with Sewage

Meanwhile, urban dwellers in Madison were battling an overwhelming problem: human waste. Early in the city's history, individual households handled their own sewage. But when a UW student discovered drinking wells had become contaminated, a sewer construction movement began.

To address the issue, private and, eventually, city-built sewer systems collected and disposed of the sewage into Lakes Mendota and Monona. The lakes did not adequately flush away the problem, however, and the stagnant waste became a major health and aesthetic concern.

After several failed attempts to treat and discharge sewage effluent into Lake Monona, the city of Madison opened the Nine Springs wastewater treatment plant in 1928. Although it employed the best technology of the time, the plant still discharged high levels of nutrients into Lake Waubesa. Finally, in 1949, urged by a group of lakeshore owners, the state legislature made the disposal of sewage effluent in the Yahara lakes illegal.

By 1958, officials established a new route for treated sewage effluent, which spared the lakes, but created a new recipient: Badfish Creek. Today, the Madison Metropolitan Sewage District still sends treated municipal wastewater into Badfish Creek, but with more advanced technology.

Agricultural Intensification

The invention of the combustion engine in the beginning of the 20th century changed everything for farming. It became more time efficient and less labor intensive. Mechanization also enabled the draining of wetlands to expand cropland, which further chipped away at Yahara's native ecosystems.

Food prices and farm profits increased into the 1920s. But increasing opportunities off the farm also led to rural depopulation and cultural change.

The New Deal began an era of increased government involvement in agriculture through subsidies and price supports. It also resulted in new conservation practices, such as contour plowing and the increased use of alfalfa, a crop that provided nitrogen for soil and nutrition for dairy cows.

Between 1940 and 1960, industrial fertilizers, pesticides, more mechanization, and the introduction of new crop varieties revolutionized agricultural productivity. The more-recent biotechnology surge, namely in genetic modification, has continued to increase productivity.

Changes in technology and rural culture, combined with urbanization, also led to the consolidation and intensification of dairy production. Between 1925 and 2010, even though 93% of Dane County's dairy farms and 31% of its cows have disappeared, total milk production has more than tripled. Increased milk production has also increased manure production.

As a consequence of agriculture's intensification, agricultural nutrient runoff has become the primary water quality threat to Yahara's lakes and streams.

Urban Expansion

The momentous 1836 decision to locate the Wisconsin Territory's capital in Madison had a lasting ripple effect on Yahara's landscape. By the start of the 20th century, as the seat of the state's government, a growing university, and a burgeoning manufacturing sector, Madison had become a major urban center.

When manufacturing began to decline mid-century, healthcare, biotech, and information technology ascended to join the state government and university as top employers. In the last several decades, growth in these sectors has substantially increased Yahara's urban footprint and the associated impervious surfaces (streets, rooftops, etc.).

As a result, urban runoff and flooding have become major problems in Yahara. With more urban surfaces, contaminants from cars and pesticides, and a chemical legacy from its industrial past, Madison and its neighboring municipalities are another important cause of poor water quality in the lakes.

Managing a Shifting, Working Landscape

After 150 years of major change on the Yahara landscape, today's land and water managers work tirelessly to lessen the impacts of our agricultural and urban footprints. Decreasing nutrient runoff from farms through new technologies, such as manure digesters, and reducing urban runoff with practices such as rain gardens are examples of these continuing efforts.

But noticeable improvements in water quality are hard to achieve, as the ongoing trends that drive change—agricultural intensification, urban growth, and climate change—continue to shift. Anticipating the possibilities for these shifts could help managers better prepare for change and make measurable progress in cleaning up Yahara's lakes and waterways.

Yahara 2070 is aimed at helping managers, decision makers, and communities anticipate and prepare for change.

Learn more about Yahara's history with the following resources:

- Forward! A History of DANE: the Capital County, by Allen Ruff and Tracy Will, edited by J. Rod Clark, Woodhenge Press, 2000

- Spirits of Earth : The Effigy Mound Landscape of Madison and the Four Lakes, by Robert A. Birmingham, University of Wisconsin Press, 2010

- Madison : A History of the Formative Years, by David V. Mollenhoff, University of Wisconsin Press, 2003