news

![]()

February 25, 2015

Policy maps may help efforts to clean up the Yahara lakes

On a patch of land upstream of Lake Mendota, where Dorn Creek meanders through farmland, local, state and federal policies are working in tandem to reduce soil and nutrient runoff into the Yahara lakes. In fact, public efforts to clean up the lakes reside in often-overlapping patches across the Yahara Watershed, a pattern made more visible by new WSC research.

On a patch of land upstream of Lake Mendota, where Dorn Creek meanders through farmland, local, state and federal policies are working in tandem to reduce soil and nutrient runoff into the Yahara lakes. In fact, public efforts to clean up the lakes reside in often-overlapping patches across the Yahara Watershed, a pattern made more visible by new WSC research.

Graduate student Chloe Wardropper and principal investigator Adena Rissman have developed a new way of looking at how multiple government efforts work together to improve lake water quality. Using the Yahara Watershed in southern Wisconsin as a case study, they mapped where on the landscape soil erosion and nutrient reduction policies are applied, providing a more holistic view that could enhance decision making.

“Thinking about policies spatially could help to improve the efficiency of efforts and funding to reduce runoff,” says lead author Wardropper, a PhD student in the UW-Madison’s Nelson Institute for Environmental Studies.

In the United States, all levels of government—federal, state, county and municipal—apply erosion and nutrient reduction policies to a landscape in a myriad of shapes and forms, including incentives (e.g. grants to implement reduction measures), regulations (e.g. land use restrictions), land acquisitions (e.g., establishing parks) and direct management practices (e.g., creating stormwater basins).

In the Yahara, a region containing both agricultural and urban land and where most water quality policies target phosphorus runoff, efforts include federal incentives for farmers to implement conservation practices on their land, state laws that limit development around lakes and rivers, Dane County parks and municipal street sweeping, among many others.

Wardropper says this “multilevel” governance system has its benefits, such as adaptability and more resources, but it can be difficult to get a clear picture of where and how progress is being made.

“Everyone is working on the same problem, but efforts may not be targeted at areas of the greatest concern,” she says.

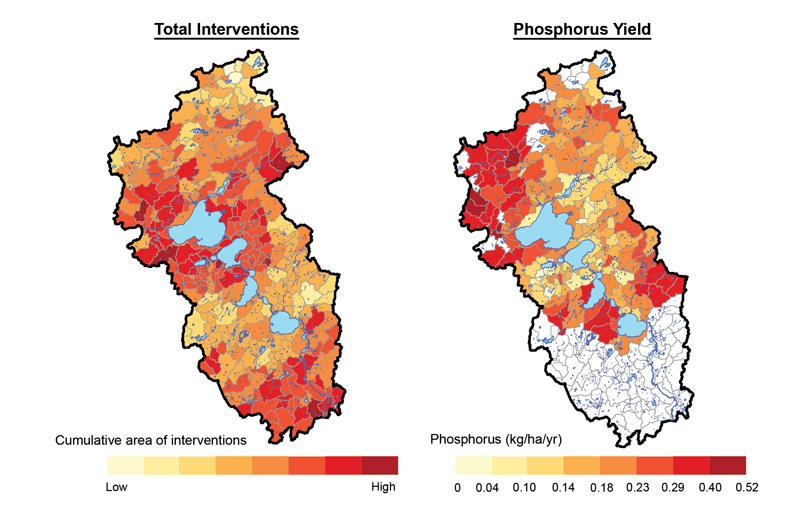

The research team mapped 35 policies to get a bird’s eye view of how they overlap and interact with each other on the Yahara landscape and to see whether they are hitting the phosphorus hotspots, or sources of large amounts of runoff. They found that, combined, the palette of policies is missing some of the most important marks.

“We found a disconnect between where policies are applied on the landscape and where the major sources of phosphorus pollution are located,” says Wardropper.

She clarified that this disconnect does not indicate that the existing policies are ineffective, an aspect they did not examine. Rather, their analysis allowed them to see the configuration of the policies and whether they are being applied in areas of greatest concern for water quality.

For example, urban areas, especially in and around Madison, contained the highest concentrations of reduction interventions, which include stormwater infrastructure, city parkland and phosphorus fertilizer restrictions. However, urban areas account for less than 30 percent of the phosphorus runoff into the four Yahara lakes.

The urban concentration may be partly a result of more money and support from urban communities, says Wardropper.

“Coordination barriers within the multilevel system can constrain efforts to target areas of concern,” she explains, adding that barriers include limited access to data due to privacy concerns and differing priorities when it comes to allocating funds.

When it comes to overcoming barriers to hitting phosphorus hotspots, Wardropper says the type of policy tool used matters.

“Different policy tools produce different results and are appropriate for different areas. In a complex landscape like the Yahara, it’s important to understand the benefits and limitations of each tool, including the area it covers and the cost and staff time needed to get it on the ground,” she says.

For example, the voluntary nature of incentive programs to reduce farm runoff does not guarantee widespread participation by farmers. Improving participation requires removing barriers, such as lengthening grant cycles to allow more time for agency staff to build relationships with farmers.

“There have been over thirty years of publicly funded efforts to reduce phosphorus in the Yahara lakes, but still no statistically significant improvements to water quality. Understanding where these diverse efforts fall on the landscape is a first step to figuring out how we can improve them,” says Wardropper.

The team emphasized that good record keeping by government agencies made their research possible. However, data sharing restrictions limited their access to information on some policies.

Wardropper and Rissman, along with co-author Chaoyi Chang, published their findings in the journal Landscape and Urban Planning earlier this year.

*The landscape pictured above is a view from Pheasant Branch Conservancy in the Yahara Watershed, with public parkland in the foreground and conservation farming practices in the background. Credit: Adena Rissman

The maps above depict the Yahara Watershed, with 300 subwatersheds. Lakes and waterways are in blue. The left-hand map shows the locations of policy applications; red indicates a high number of policies covering a subwatershed. The right-hand map shows areas of high (red) and low (yellow) phosphorus runoff; white indicates no data available. As an example of disconnection between the number of policies applied and phosphorus hotspots, look to the Madison isthmus between the top two lakes. Source: Wardropper, Chang, & Rissman, 2015