news

![]()

January 15, 2015

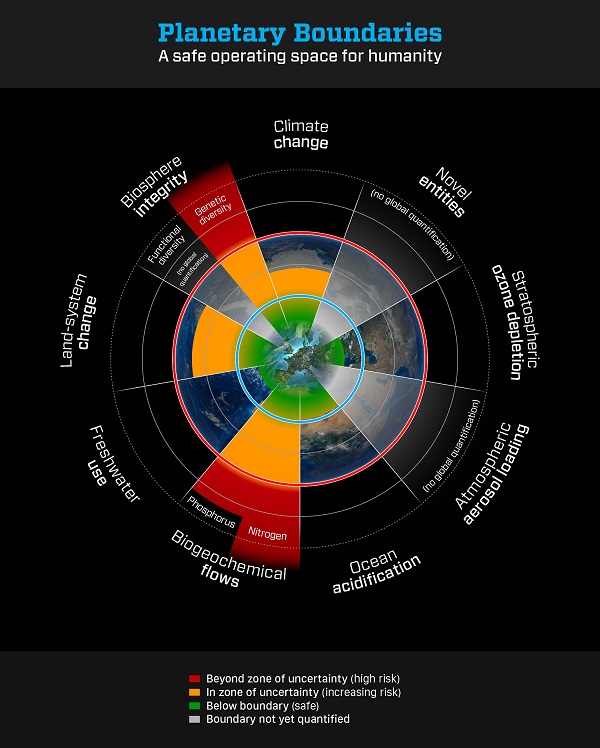

Humanity crosses 4 of 9 'planetary boundaries'

Civilization has crossed four of nine “planetary boundaries” due to human activity, according to an article published in the journal Science. An international team of 18 researchers, which includes WSC PI Steve Carpenter, claim climate change, the loss of biosphere integrity (e.g., biodiversity loss), land-system change (e.g., deforestation), and altered biogeochemical cycles (e.g., phosphorus and nitrogen runoff) have all passed beyond levels that put humanity in a “safe operating space.”

Civilization has crossed four of nine “planetary boundaries” due to human activity, according to an article published in the journal Science. An international team of 18 researchers, which includes WSC PI Steve Carpenter, claim climate change, the loss of biosphere integrity (e.g., biodiversity loss), land-system change (e.g., deforestation), and altered biogeochemical cycles (e.g., phosphorus and nitrogen runoff) have all passed beyond levels that put humanity in a “safe operating space.”

Carpenter says the study should be a wake up call to policymakers that “we’re running up to and beyond the biophysical boundaries that enable human civilization as we know it to exist.”

For the last 11,700 years, Earth has been in a “remarkably stable state,” says Carpenter. During this time, known as the Holocene epoch, “everything important to civilization,” has occurred. From the development of agriculture, to the rise and fall of the Roman Empire, to the Industrial Revolution, the Holocene has been a good time for human endeavors. But, over the last century, some of the parameters that made the Holocene so hospitable have changed.

Climate change, of course, is one of those things, as is a troubling loss of biodiversity. But Carpenter’s contribution to the report has to do with two elements essential to life: the chemical elements phosphorus and nitrogen.

Both phosphorus and nitrogen are widely used to fertilize crops, and the rise of large-scale, industrial agriculture has led to an immense increase in the amount of the chemicals entering our ecosystems.

“We’ve changed nitrogen and phosphorus cycles vastly more than any other element,” Carpenter says. “[The increase] is on the order of 200 to 300 percent. In contrast, carbon has only been increased ten to twenty percent, and look at all the uproar that has caused in [the] climate.”

The increase of phosphorus and nitrogen has been especially detrimental to water quality. Phosphorus loading is the leading cause of both harmful algal blooms and the oxygen-starved “dead zone” in Lake Erie. Likewise, nitrogen flowing down the Mississippi River is the main culprit behind the dead zone in the Gulf of Mexico.

The bottom line is that nitrogen and phosphorus levels are way beyond the boundaries of what they were during the Holocene. But, Carpenter says, that chemical load isn’t spread evenly over the planet.

“There are places that are really, really overloaded with nutrient pollution,” he says. These places include Wisconsin and the entire Great Lakes region.

But there are other places, such as much of Africa, that are under-supplied with nitrogen and phosphorus.

“We’ve got certain parts of the world that are over-polluted with nitrogen and phosphorus, and others where people don’t even have enough to grow the food they need,” says Carpenter.

Carpenter calls it a “distribution problem” and says that places like the Midwestern U.S. could vastly reduce its use of fertilizers and still maintain productive crops, while nutrient poor regions of the globe could increase their use, all while keeping the global levels safely within the study’s prescribed “planetary boundary.”

“It might be possible for human civilization to live outside Holocene conditions, but it’s never been tried before,” Carpenter says. “We know civilization can make it in Holocene conditions, so it seems wise to try to maintain them.”

The study, entitled "Planetary boundaries: Guiding human development on a changing planet," was published in the January 15, 2015 issue of Science. The researchers discussed the study at the 2015 World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland.

*Image credit: Steffen et al, 2015